Dev Journal

Absolute: Origin Story

From Bad Ideas a Good Card Game Arises

Aug 03, 2025

Back in early 2024, we played the Star Wars-universe game called Sabacc. Featured in the movie Solo, this is a game that's similar in essence to poker, but with a blend of baccarat and blackjack. Betting was the main driver of the game - which honestly, is much of what poker is, too.

It used a set of cards that included positive and negative cards, three different types of suits, and multiple imagery cards (like the Jack, King, and Queen in a normal poker deck). The first mechanic of the game was simple: to build a hand with a value of zero. But then came the numerious (and I do mean numerous) combinations of cards you could play. Just like poker has pairs, 3 of a kind, etc., this game had it's own version of these combinations, but far more complicated due to the positive and negative card mixture. Not knowing when to say "enough," they also added a die that would essentially force everyone to start the hand over.

It was... not a good game. It had too many complicated rules; too many things to keep track of. And it basically throws strategy right out the window with a single roll of the die.

What we did end up liking was the idea of a game that had positive and negative cards and would used the summing to zero mechanic. That wasn't something we'd seen often. That same weekend, we ended up trying two other card games - one that came down to luck of the draw, and another that was essentially solitaire with friends, in that it didn't matter what you did, you couldn't affect the outcome for others. So there was no interaction.

It got me thinking: can we build a game with an straight-forward goal, mechanics that allowed for strategy rather than luck, and interaction between players?

We started by printing a basic set of positive and negative cards, 0-10, with three signs. This yielded 66 cards. We hadn't realized at first that we printed positive and negative copies of the zero card, but thought that might make things interesting: what if zero was more than just zero? What if it was a wildcard, but instead of just being any value, it had to be the sign on its card - so a negative zero had to be a negative number? That would definitely be more interesting than just being any number, or just a zero which wouldn't affect the value of the hand at all.

So, we kept them. Then we started to make rules and play short games. We tried starting with different numbers of cards, changing how many cards you could hold in your hand, how many you could discard in a round, and how many you drew. These were all basic card game mechanics that were easy enough for anyone to understand; just a matter of getting the numbers right.

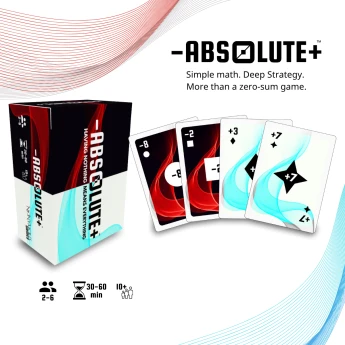

After a lot of internal testing, we came up with starting with 5 cards, drawing 1 every round, and holding a max of 7 cards. The max cards was important, as it forced people to either discard or play sets sooner than they would otherwise. A played set of cards (summing to zero) had to have at least 3 cards - this prevented people from just placing a pair of positive/negative numbers. We also changed the suits (to be more distinguishable) and added a fourth suit so we had a better card distribution - 88 cards, positive and negative 0-11, with circles, diamonds, squares, and stars. This many cards also allowed us to take the game up to 6 players rather than 4.

At this point the game played but there was no interaction, and it was a pretty boring basic math game. I don't recall how we hit upon it, but we liked the idea of making the game about scoring points more than just adding to zero. Adding to zero was a means to an end: the way of playing a set of cards. But the points - the value of the set - that would change what people played, and which cards they went after.

We started by making the set worth the sum of the absolute value of all the cards in the set. So if you had -7, +3, and +4, your total was 14. But this would yield only even values. Next, we made it so that the highest absolute number would be the score for the set, and you could get extra points if your set had other things in a set. We played around with what those "things" were, and ultimately came up with:

- +1 per card over three cards in the set

- +1 for each card in a positive or negative run (series) of 3 or more cards

- Double the set's value if you had 4 or more of the same absolute number

- Double the set's value if a set was all the same suit

To prevent zero cards from unbalancing the deck, we made it so that when scoring, we only looked at the absolute number on the cards, which means that a zero card - even when representing another number like 10 - was still a zero.

Now the goal was to make the most points over multiple rounds of play, and the game started to get interesting. People discarded and played different cards, but we still had no interaction.

I came up with the idea of being able to swap cards from the sets that were played on the table. This would allow you to hurt another player's points, get cards you might need, or both. At first you could swap any number of cards, but then we realized this quickly broke the game, in that you could just take a set from your hand and swap it with an already played set. So we limited the swapping mechanic to up to two cards from your hand with up to two cards in a played set. That set still had to be legal as well (sum to zero). This made it trickier, but far more strategic in how you performed your swaps.

The game at this point was coming together well. We started playing with others, and they were liking it. But something was still off. We realized that even though we'd added strategy by making the goal about points, and interaction by allowing card swaps, the luck component - due to the randomness of the cards - was outweighing the other elements of the game. You could be dealt a complete set and go out on your first turn.

To limit this, rather than playing just a single set to end of round, you had to play at least 3 sets, and discard your last card. This would do a few things:

- It prevented a lucky draw from ending a round quickly.

- It made it so that you had to have some sets played and vulnerable to swapping because you couldn't hold on to all the cards needed for three sets (given the 7 card hand limit).

- It allowed us to add the regrouping ability: now with multiple sets played, you could play cards and regroup your sets into new/better sets worth more points. This added another layer of strategy in that you had access to more cards over time.

The last thing we did was add the concept of locked sets (the inability to swap with someone's played sets). The reason for adding this was because once someone went out - played at least three sets and discarded their last card - they had no way to respond if someone swapped cards from their sets. So to prevent this, for anyone who went out their sets were considered "locked." If you didn't go out because you had cards left or didn't play enough sets, the next person could still mess with your sets before the end of the round.

Nearly a year had gone by. There was still a lot to do - finalize the design of the deck, the rulebook, the box, and tons and tons of playtesting - but we were confident in the game itself. We had done what we set out to do: it was a card game that used simple math and combined it with round-to-round evolving strategic and interactive play. It kept the "luck" from the shuffled deck, but tamped it down through the swapping and regrouping mechanics. New strategies would occur in almost every playthrough. Most of all, it was fun. And that was the overarching goal we always kept in sight.